At the end of 1972, shortly before his trial, Watergate burglar James McCord feared that both he and the CIA were being framed by the government for the Watergate operation to protect the White House.

Unease turned to paranoia during a lunch meeting with his lawyer Gerald Alch on December 21st, at which it became clear the attorneys for the burglars were exploring a common defense that the Watergate break-ins were a CIA operation. Rolando Martinez was still on a CIA retainer at the time of his arrest, Bernard Barker had been a contract agent for the Agency during the sixties, while Howard Hunt and McCord had retired from the CIA in 1970.

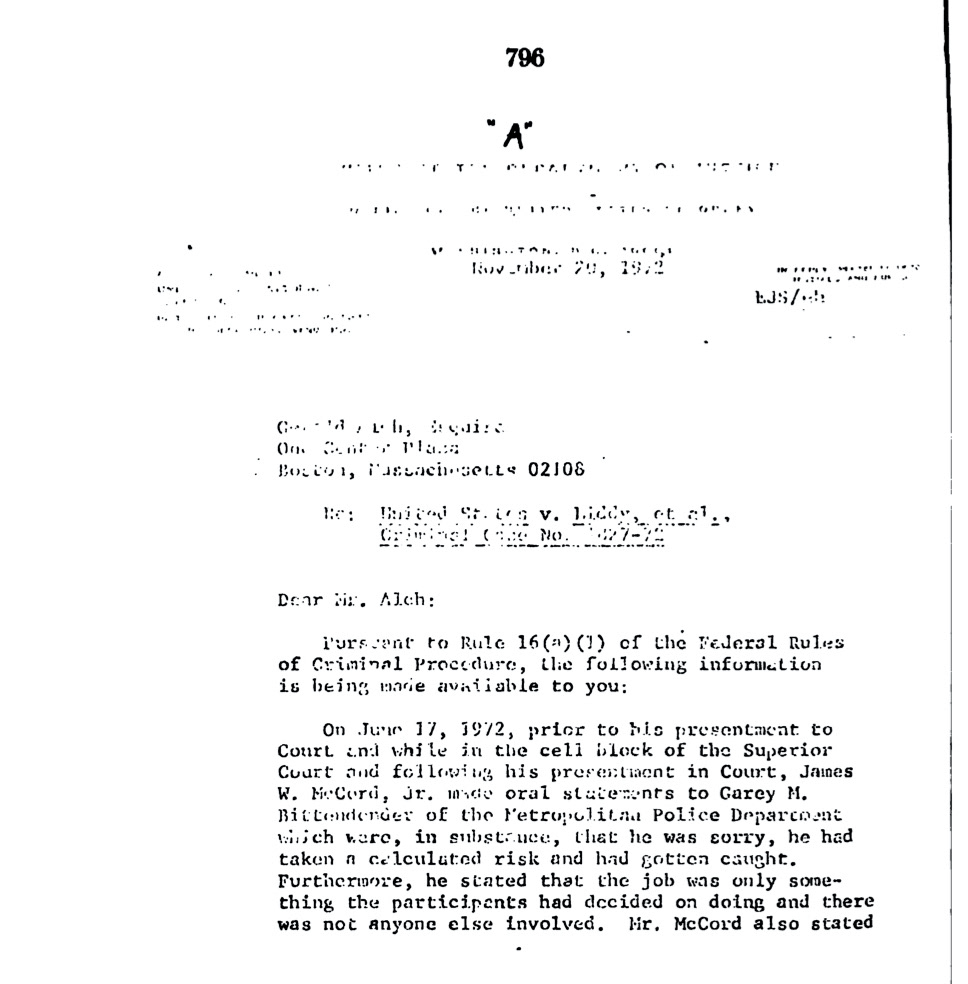

Over the holidays, McCord sent a series of letters to former CIA colleague Paul Gaynor, warning him the “fix” was in. One of his key concerns was a letter lead prosecutor Earl Silbert had sent Alch on November 20th, during pre-trial discovery:

Silbert letter to Alch, 20 November 1972

Silbert letter to Alch, 20 November 1972

On June 17, 1972, prior to his presentment to Court and while in the cell block of the Superior court and following his presentment in Court, James W. McCord, Jr. made oral statements to Gary M. Bittendender (sic) of the Metropolitan Police Department which were, in substance, that he was sorry, he had taken a calculated risk and had gotten caught. Furthermore, he stated that the job was only something the participants had decided on doing and there was not anyone else involved. McCord also stated that all the others involved were old friends of his and were very good in their trade [2 words illegible] retired CIA men who have families in and around Miami, Florida. When asked if he had known E. Howard Hunt, he stated in substance that the name has been heard around. [1]

McCord letter to Gaynor, 22 November 1972

McCord letter to Gaynor, 29 November 1972

McCord told Gaynor he needed “evidence of perjury” by Bittenbender before the trial – “I know he is lying.” [4]

Surprisingly, until I contacted him recently, no researcher or investigator had spoken to Garey Bittenbender about his meeting with McCord since July 1972, and Silbert’s letter to Alch summarising the meeting had lain buried in a congressional report for forty-five years.

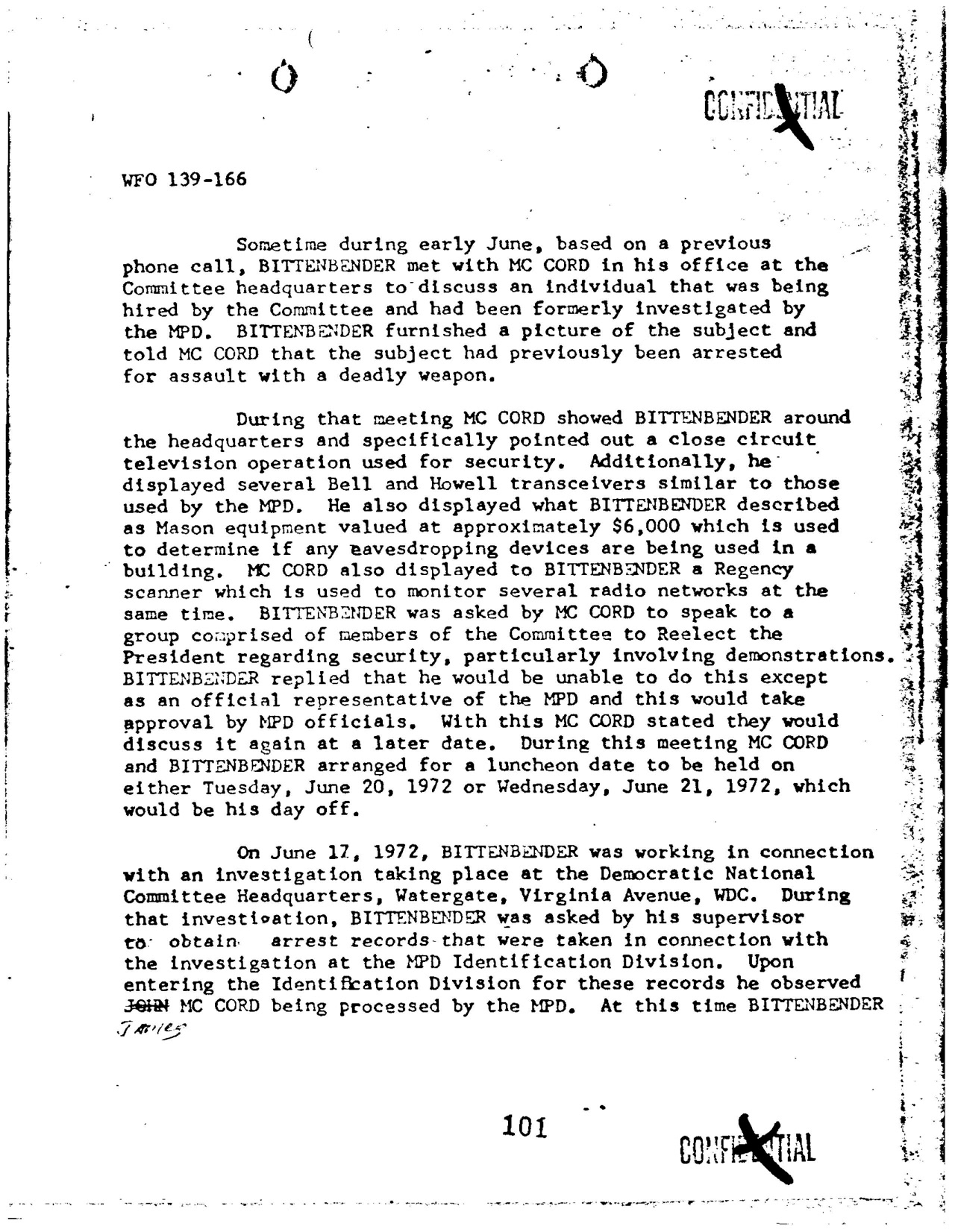

Bittenbender first met McCord in March 1972. McCord was security chief for the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP) and Bittenbender advised him that a demonstration was due to take place in front of his office. Bittenbender was a 23-year-old plainclothes officer in the Intelligence Division of the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). His twin brother Ronald was also with the department.

A week later, McCord contacted Bittenbender to establish a liaison between CRP and the MPD Intelligence Division. His supervisor approved and he continued to share intelligence with McCord about demonstrations which might impact the security of CRP and the Republican National Committee. [5]

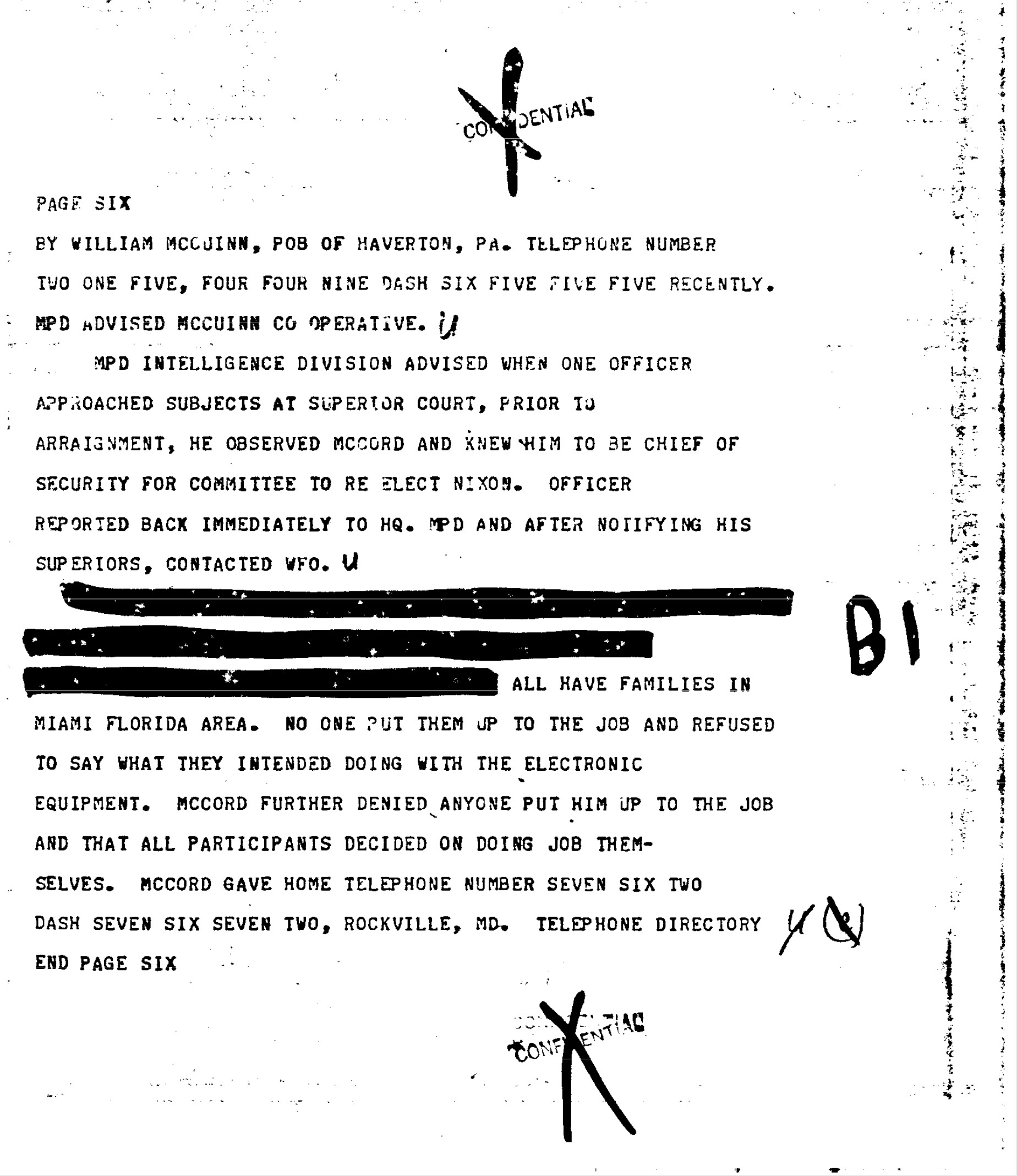

FBI report, 17 June 1972

FBI summary of interview with Bittenbender, 17 July 1972

FBI summary of interview with Bittenbender, 17 July 1972

FBI summary of interview with Bittenbender, 17 July 1972

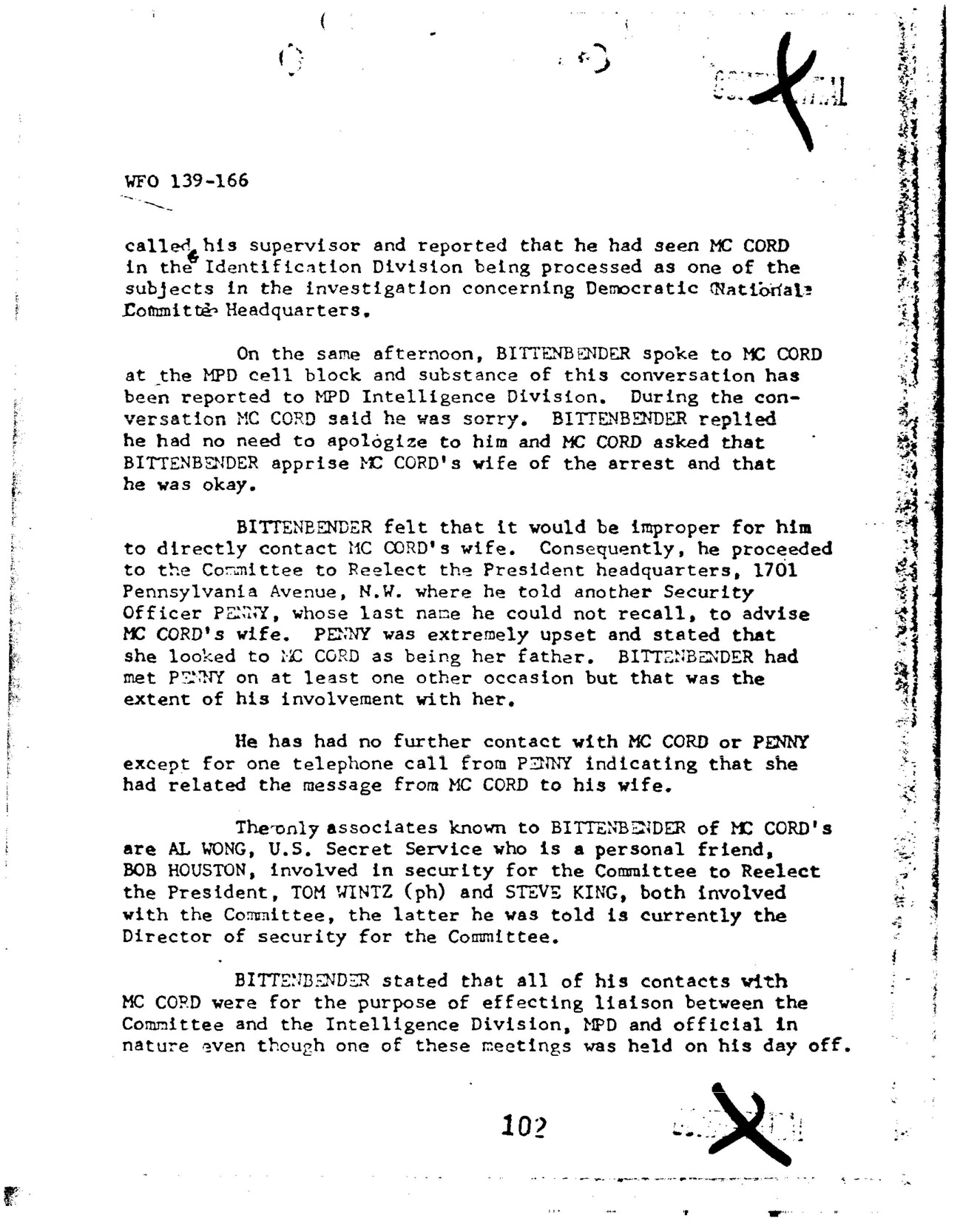

On his day off in early April, Bittenbender met McCord for lunch and in early June, they met again at CRP headquarters to discuss a prospective CRP employee who “had previously been arrested for assault with a deadly weapon.” McCord showed Bittenbender around and pointed out a closed-circuit television operation used for security, several transceivers like those used by MPD and an anti-eavesdropping device. McCord asked Bittenbender to brief members of CRP about security issues around demonstrations but Bittenbender said he would need to get approval. They arranged to have lunch again on June 20th or 21st on Bittenbender’s day off. But of course, this never happened. By then, McCord was in jail. [6]

Recalling McCord today, Bittenbender describes him as “likeable and easy going…[with] a genuine interest in his work. He had told me of his past career and his current status as retired from the CIA.” After the arrests at the Watergate office building on Saturday morning, June 17th, Bittenbender’s supervisor sent him to the identification section of MPD headquarters to get the names of the arrested men and any other relevant information:

Upon my arrival at the processing area I immediately recognized James McCord as one of the individuals who were at a counter providing handwriting samples as a process of their arrest. [7]

The arrested men all gave operational aliases but Bittenbender knew “Edward Martin” was really James McCord. He took the false names back to the Intelligence Division and “advised [his] supervisor of the identity of James McCord and his relationship to the Committee to Re-elect the President”:

I do remember telling him this was going to be one hell of an incident as I could see the implications. I was the first person to identify any of the persons arrested. I know that this information was passed up the Chain of Command to the Chief of Police.

After assuring his supervisor he was “certain of the identification,” Bittenbender was “sent to interview McCord at the cell block of the US District Court where he was being held prior to his court processing”:

I was a bit surprised that they wanted me to interview McCord at the Court. I suspect that since I knew him they felt that I may be able to get additional information which would help the Department in its investigation. In that interview, I asked McCord who were the other individuals arrested with him. He advised me that they were former CIA operatives some of which were involved in the Bay of Pigs incident. I specifically asked if this was a CIA related incident at the Watergate. His reply to me was that it WAS NOT.

During the interview, McCord apologised and asked Bittenbender to notify his wife of his arrest and that he was okay. Bittenbender felt it would be improper for him to call McCord’s wife, so as McCord was taken to his arraignment, Bittenbender visited the offices of CRP and asked security officer Penny Gleason to call her instead. Gleason was extremely upset to hear of McCord’s arrest and said McCord had been like a father to her. Bittenbender submitted a written report of his interview with McCord when he returned to the office that day and this was subsequently shared with the FBI and prosecutors and forms the basis of Silbert’s letter to Alch.

When Bittenbender’s alleged claim came up during the Senate Watergate hearings, Inspector Albert Ferguson, chief of intelligence for MPD, said Bittenbender’s notes “indicate only that he knew that McCord was a former CIA agent, not that he had been told the break-in was a CIA operation.” [8]

By now, McCord had a new attorney and was accusing Alch of pressuring him into going along with a CIA defense:

There followed a suggestion from Alch that I use as my defense during the trial the story that the Watergate operation was a CIA operation…I could ostensibly have been recalled from retirement from CIA to participate in the operation…[and] that if so, personnel records at CIA could be doctored to reflect such a recall…[James] Schlesinger, the new Director of CIA, whose appointment had just been announced, "could be subpoenaed and would go along with it." [9]

Alch vigorously denied the allegations but the myth that McCord told Bittenbender the Watergate break-in was a CIA operation will not die. A new book by Mark Felt’s attorney John O’Connor makes hay with the Bittenbender allegation in a very sloppy manner. O’Connor mistakenly claims the alleged statement was included in the FBI report summarising an interview with Bittenbender and that this was the key document given to McCord’s lawyer (it was not). [10]

Reflecting on his minor role in Watergate today, Bittenbender is still amazed he got caught up in the scandal. While it’s now a source of amusement, at the time, he “was much more alarmed about it.” He can't locate his original report on the interview with McCord and the MPD no longer has its Watergate files but Silbert’s letter to Alch and Bittenbender’s memories of his encounter with McCord that day should lay another Watergate myth to rest.

Notes:

[1] “Inquiry into the Alleged Involvement of the Central Intelligence Agency in the Watergate and Ellsberg Matters” (aka The Nedzi Report),

1975: 791, 796-7. Parts of the letter are almost illegible but this is my best guess.

1975: 791, 796-7. Parts of the letter are almost illegible but this is my best guess.

[2] McCord letter to Gaynor, 22 December 1972.

[3] McCord “notes” to Gaynor, 29 December 1972.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Bittenbender FBI interview summary, 17 July 1972; Bittenbender email to author, 17 April 2020.

[6] Bittenbender FBI interview summary.

[7] Bittenbender email to author. According to Jim Hougan, the identification was made around 10 a.m. (Hougan, Jim. Secret Agenda. New York: Random House, 1984, 218).

[8] Edwards, “McCord Disputed on Idea of Linking Burglary to CIA,” Washington Post, 23 May 1973, A12, cited in O’Connor. McCord’s book contains a brief chapter on Bittenbender (McCord, James W. A Piece of Tape, Rockville, MD: Washington Media Services, 1974, 50).

[9] McCord testimony at Senate Watergate Committee Hearings, 18 May 1973, Book 1, 194.

[10] O’Connor, John. Postgate: How the Washington Post Betrayed Deep Throat (New York: Post Hill Press, 2019). See also Alch testimony at Senate Watergate Committee Hearings, 23 May 1973, Book 1, 313.